By Don Heller, Gigi Jones, and Abby Miller

The recent dismantling of affirmative action and the COVID pandemic highlighted the barriers preventing underserved, underrepresented students – students of color and those who are low-income and first-generation – from enrolling in college. A college degree is the pathway to social mobility for families trapped in the cycle of poverty. However, the rising costs of college are increasingly out of reach for many students.

Financial aid discussions have centered on simplifying FAFSA and increasing federal Pell Grants – all important – but federal student aid policies are only one funding source for families trying to determine how to pay for college. Further, Pell Grants cover just under one-third of tuition and fees at the average four-year, public college in the nation, leaving families to cover the remaining two-thirds of tuition, along with living expenses, books, and other costs. This leaves, on average, over $15,000 a year for students and families to fund, many of whom lack savings and may be living paycheck to paycheck. Institutions can also do their share to make college more affordable.

Shifting the Conversation to Institutional Aid

Most higher education institutions have a high tuition, high aid model – the expectation is that students will not pay sticker price; rather, institutional grants will help cover unmet financial need after other sources of aid, which offset the total cost. However, the reality is these institutional grants are not fairly distributed. The data below highlight disparities in institutional merit (academic and other non-need-based scholarships) and need-based grant awards.[1] This preliminary analysis is part of a forthcoming study using the recently released 2019-2020 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20). Data included in the analysis are for dependent students attending public and private not-for-profit four-year institutions.

College Access Challenges

Students of color and those from low-income families face a range of financial and academic barriers to college access. They typically attend K-12 schools in underfunded school districts with higher student-to-counselor ratios, a lack of college and standardized testing guidance and tutoring, and less access to college preparatory coursework.

Most states have need-based grant programs to help fund college costs, but these vary widely in their requirements and size of the grants – many are a combination of both need- and merit-based. Most institutions provide need-based scholarships as well, but these also vary widely in structure and generosity. Oftentimes low-income students rely on loans they are stuck paying back over many years, even decades. In addition, many low-income students work numerous hours while enrolled to help pay for college, attend part-time, and drop out due to work, family, and financial demands.

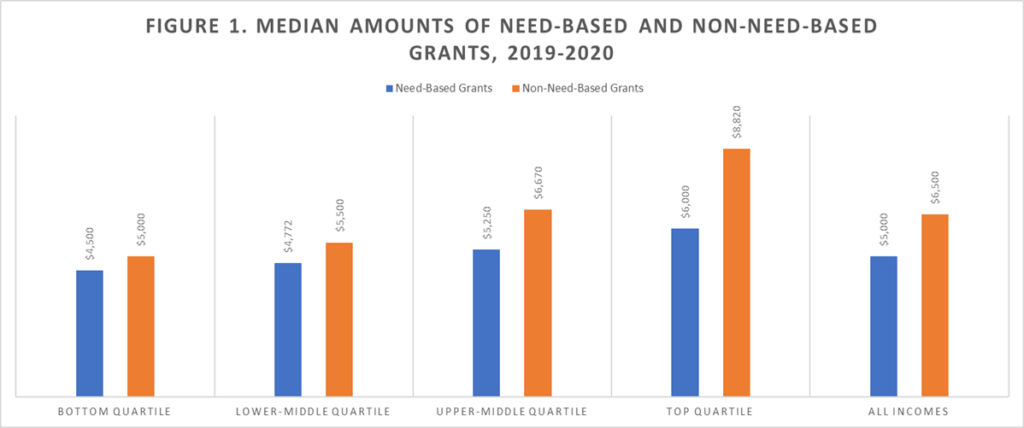

Institutional Aid by Income

As Figure 1 below shows, both merit-based AND need-based grants are larger for higher-income students, and the awards increase incrementally with each income quartile[2]. The lowest-income students receive only $4,500 in need-based grants and $5,000 in merit-based grants, compared with $6,000 and $8,820 for need- and merit-based, respectively, in the highest-income quartile.[3]

Source: Unless otherwise noted, all data used in the study are from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20).

Source: Unless otherwise noted, all data used in the study are from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20).

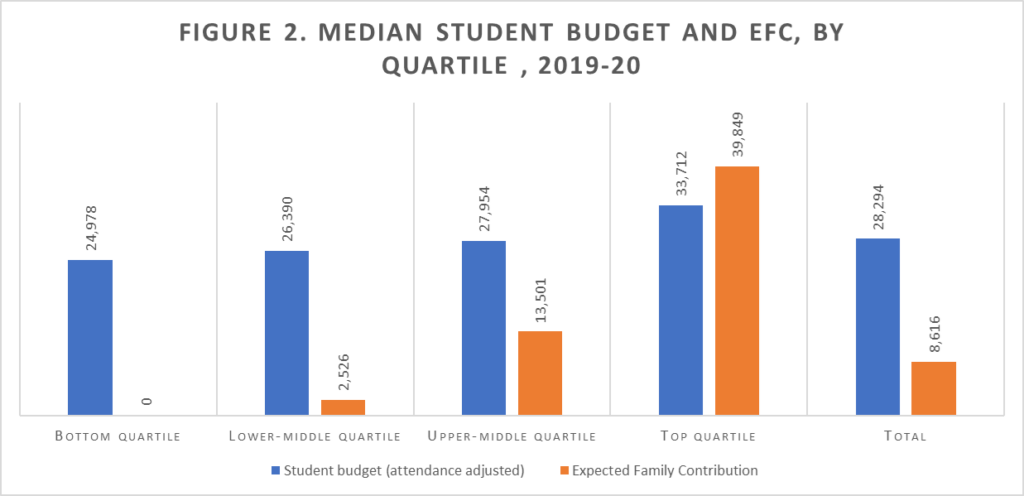

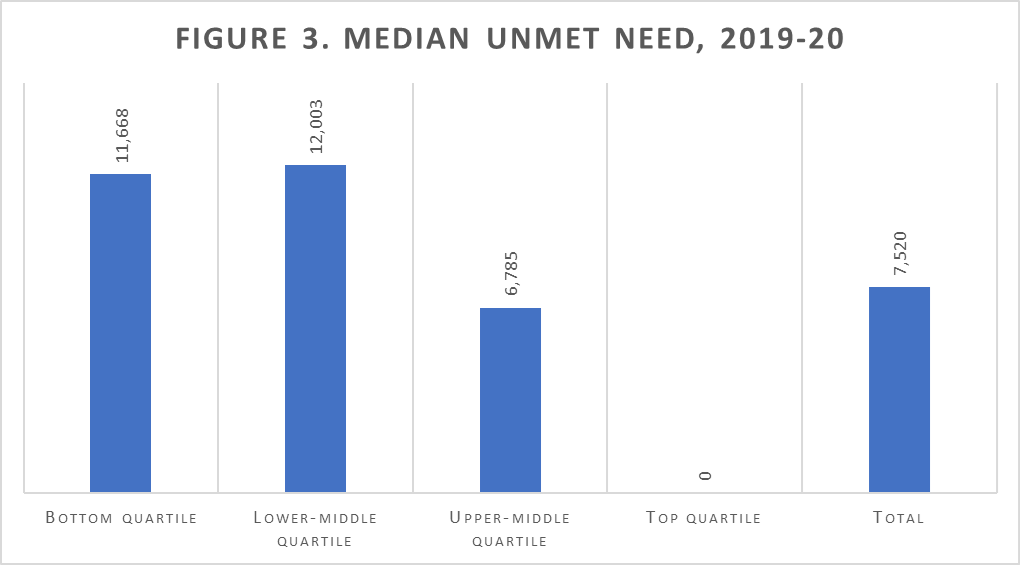

Part of the reason for the top quartile receiving larger grants is because they attend higher-priced institutions (Figure 2). However, the top quartile also has the largest expected family contribution (EFC), an estimate of a family’s ability to fund tuition used in the federal financial aid formula. As the figure below displays, students in the lowest income quartile have a median EFC of $0. Therefore, while their total budget (tuition, fees, expenses) is lower than higher-income students, they lack the parental financial resources to pay for expenses out of pocket. As a result, their unmet need (the total budget, minus EFC and grants) is much higher than higher-income students (Figure 3), while the median unmet need for the highest quartile is $0. In other words, between family funds and grants, the expectation is that wealthy students can pay for higher education without having to take out loans or work while enrolled. Lower-income students, however, require additional financial aid resources to pay for a college experience that is similar to their higher-income peers.

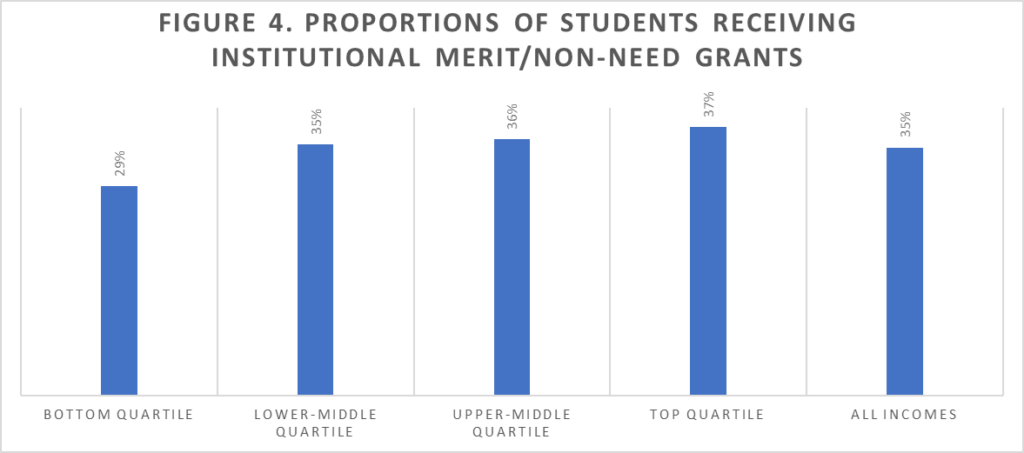

Higher-income students not only receive larger grants, but they are also more likely to receive merit-based aid: 37 percent in the top quartile receive merit-based aid compared with 29 percent of the neediest students (Figure 4).

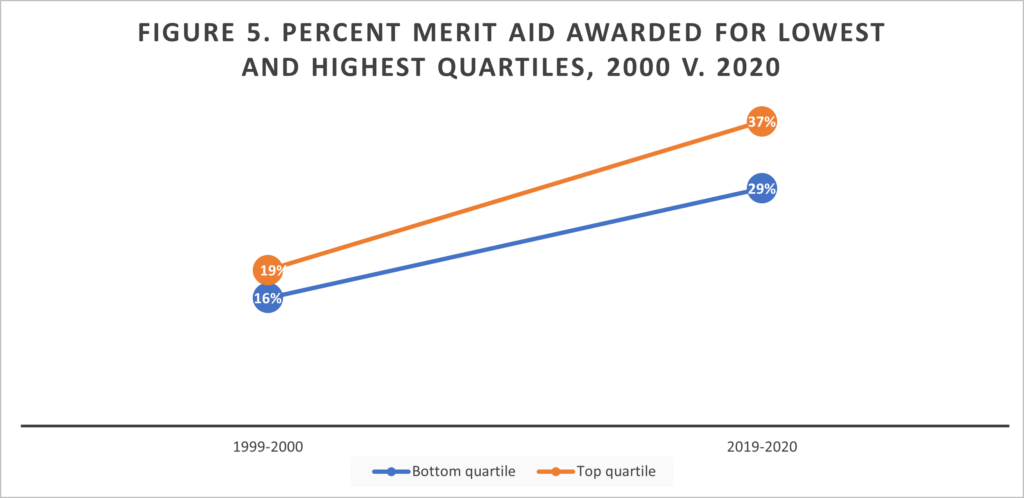

The disparity in merit-based institutional aid award has persisted – and widened – over time. As Figure 5 below displays, the percentage-point gap was 3 percentage points two decades ago, in 2000, and that gap widened to 8 percentage points in 2020.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1999-00 and 2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:00, NPSAS:20)

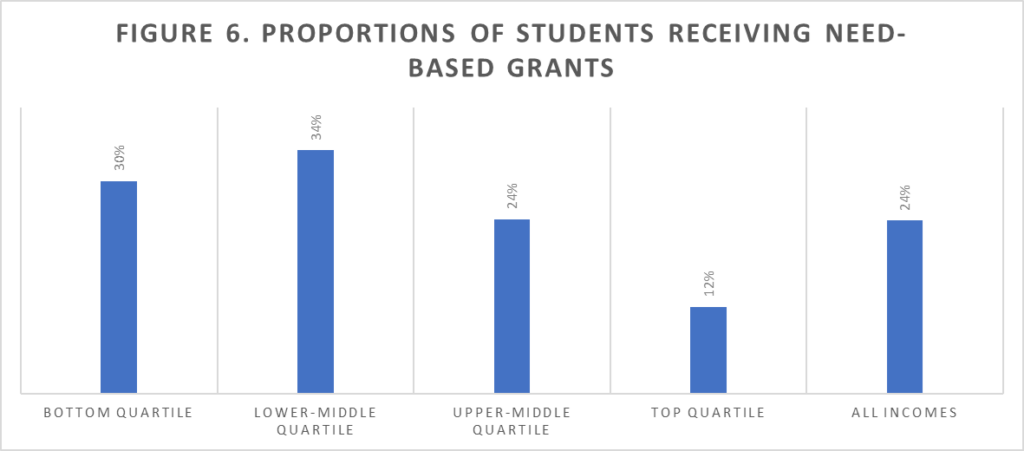

While lower-income students are generally more likely to receive institutional need-based grants than their higher-income peers, notably, 12 percent of students in the highest-income quartile receive need-based grants (Figure 6). Additionally, the lower-middle quartile is the most likely to receive need-based grants, 34 percent, compared with 30 percent in the bottom quartile.

Institutional Merit-Based Aid by Race/Ethnicity

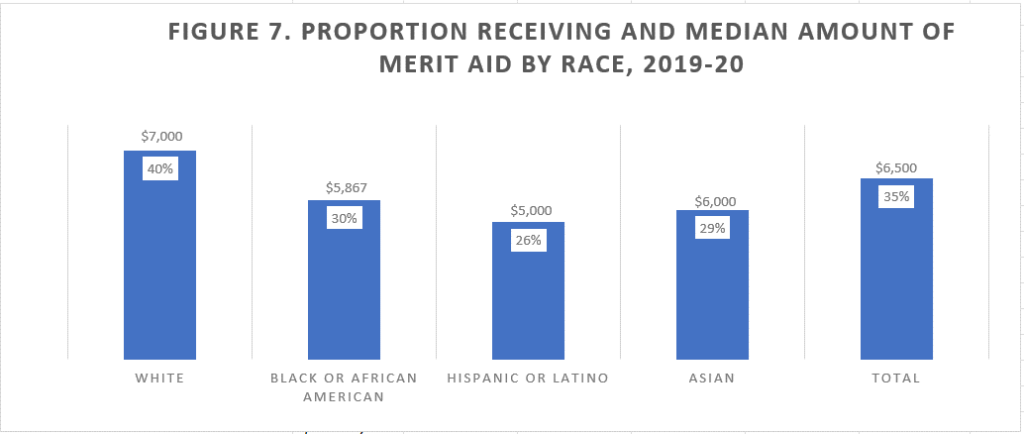

Differences in institutional aid receipt and amounts also exist by race/ethnicity. White students are the most likely to receive institutional merit-based aid, and receive higher awards than Black, Hispanic, and Asian students (Figure 7).

Questions to Consider

This preliminary analysis raises interesting questions about the use of institutional grants. For example, are merit-based scholarships intended to boost a college’s rankings by luring the highest achieving students? What if institutions shifted these dollars to students who truly need financial assistance to attend college?

This analysis concurs with past research that merit-based scholarships primarily benefit wealthier students (see Heller 2006, Miller 2023, Price 2001). The topic of institutional financial aid policy often takes a backseat to the federal aid policy conversation. And while Pell Grant increases are important, they are not enough, particularly today when the wealth divide continues to grow. While in the 2019-20 academic year federal Pell Grants awarded totaled $26 billion, institutions provided over $52 billion in grant aid to undergraduates, thus confirming the critical role that institutional aid policies play in promoting college access and completion (College Board, Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid, 2022).

Institutions must balance using merit-based aid to increase rankings with need-based aid to serve as engines of economic equality and mobility. Now without the use of affirmative action, institutional aid can also be a way to increase the representation of historically underserved students (institutions should work with their legal counsels to understand how the U.S. Supreme Court decision would apply to any race-based aid programs). Perhaps colleges and universities can do both – to reward high-achievers while adjusting the amount based on a student’s remaining need. Certainly, this is a complex topic that requires stakeholders and policies at all levels – institutional, state, and federal – to make systemic changes. Clearly our priorities must be shifted when the wealthiest Americans receive more institutional scholarship money than those with the most financial need.

Future Research

Additional analysis is forthcoming as part of a larger study that will explore additional factors behind institutional aid awards, cost of attendance, unmet need, loans, student employment patterns, and attendance and enrollment patterns.

Donald E. Heller is the retired provost and vice president of academic affairs at the University of San Francisco (CA). He is currently working as an independent higher education consultant. Gigi Jones is an independent higher education consultant who has worked for several higher education organizations, including ACE, NAICU, NASFAA, and the IPEDS program at the U.S. Department of Education. Abby Miller is a partner at ASA Research, a small women-owned firm focusing on college access and success for marginalized students.

[1] This analysis uses the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. Institutional non-need and merit grants are defined as grants and scholarships based entirely on merit or other circumstances not related to need, including athletic and merit scholarships, tuition waivers and categorical grants, institution military/armed force grants, and institution veterans’ education benefits. Institutional need-based grants are defined as both need-based grants and need-based grants that also have a merit component.

[2] NPSAS income quartiles are assigned relative to other students of the same dependency status. Income for dependent students is based on their parents’ income. The approximate parental income ranges for dependent students’ income quartiles are as follows: 1) less than $30,100, 2) $30,101 to $68,500, 3) $68,501 to $129,800, and 4) more than $129,800.

[3] Note: Median amounts have been used due to high outliers. Data included in the analysis are for dependent students attending public and private not-for-profit four-year institutions.